For most field soldering situations installing copper rain gutters I use a propane torch with 50/50 solder. Some will say this leaves burn marks but I say that doesn't matter after a few days. We have gotten proficient with sweating the soft solder through the joints in this manner. Key is a proper temp.

When the flame is too high the solder runs like water and the metal contorts. When it is too low there is a poor bond. I use a small propane canister with a flexible hose. The tank is small enough that I can keep it in my tool bag and if you have ever tried to iron solder three stories in the air in a high wind you'll know it is difficult at best. We do have the luxury of a warm climate here in Southern California so we do not deal with the expansion and contraction some installers do.

When the situation calls for iron soldering I usually am working at a bench producing rectangular soldered downspouts. In this situation I do use a traditional soldering iron. I keep powdered sal ammoniac to mix with water as I like a hot, cleaned, tinned iron. The only trick I can think of is that I tin the irons with a lead free solder that has a much higher melting point as this seems to keep them clean longer. I also remove the irons from the flame when not in use as carbon builds on the iron ( which is actually a chunk of shaped copper ).

People call me all the time with questions about copper gutters and soldering. I am hoping that by the public using this portion of my website to ask these questions I can share the information with everybody. I have nothing to lose my sharing my experience.

Description

This section is from the book "Practical Sheet And Plate Metal Work", by Evan A. Atkins. Also available from Amazon: Practical Sheet And Plate Metal Work.Chapter XXXV. Sheet Metal Joints

There are really only five ways in which the edges of sheet and plate metals can be fastened together - viz., by soldered, brazed, welded, grooved, and riveted joints. But whilst we are limited to the use of one or other of these forms of jointing, there are numerous modifications of them in practice.

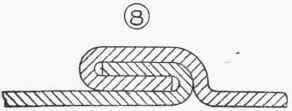

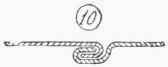

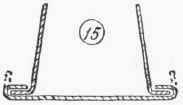

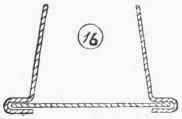

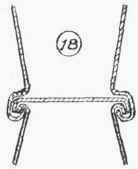

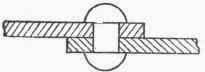

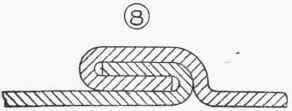

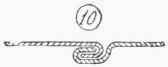

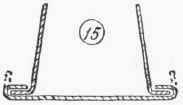

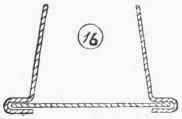

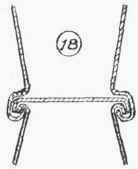

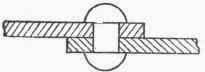

The sketches of joints shown are enlarged somewhat, to better exhibit the layers of metal. (1) shows the ordinary lap-joint, as used in soldering together the edges of tinplate, zinc, or galvanised iron, the width of lap running from about 1/8 in. in thin tinplate up to ¼ in. in galvanised iron.

To make a soldered joint is not a very difficult matter; but there are a few things that want to be taken notice of if the job is to be carried out successfully. The fluxes (anything that is used to assist the flow of metals) used are various; but those commonly in use are "killed spirits," and ready-prepared soldering fluids. "Killed spirits," or "spirits of salts," as it called, takes a good deal of beating for all-round work, as by its use almost any metal can be soldered, with the exception, perhaps, of aluminium. It is prepared by dissolving as much scrap zinc as possible in hydrochloric acid, the resulting liquid being known chemically as a solution of chloride of zinc. If the edges of the metal are clean, they can be lapped over without any preparation, and the spirits applied along the joint with a brush about 1/8 in. wide - a good brush can be made with a few bristles fixed into a strip of double-over tinplate. Before using the soldering-bit it should be seen that it is

properly tinned, and if not, get to dark-red heat, file the point about | in. along, dip in spirits, and then apply solder.

properly tinned, and if not, get to dark-red heat, file the point about | in. along, dip in spirits, and then apply solder.

The mistake that the novice usually makes in soldering a joint is to stick the metal on like glue or putty, instead of holding the soldering-iron long enough against the joint for the solder to be properly melted and the joint to get sufficiently hot for the solder and sheet metal to firmly adhere together. Instead of using the extreme point of

the soldering-iron to run the solder on joint, an edge of the square point should be used to draw along the solder. In this way a greater quantity of heat will be transmitted to the joint, and thus a better and quicker job made.

the soldering-iron to run the solder on joint, an edge of the square point should be used to draw along the solder. In this way a greater quantity of heat will be transmitted to the joint, and thus a better and quicker job made.

The soldering-iron must be watched, so that it does not get red-hot, or else the tinning on its point will be burnt off, or, what is worse, form a hard skin of bronze, which is somewhat difficult to file away. When the soldering-iron is drawn from the fire it can be cleaned by quickly dipping the point into the spirits, and also in this way one can judge as to its proper temperature. If when dipping the iron into the spirits much smoke is given off, or the liquid spurts about, the iron is too hot; or, on the other hand, if small bubbles of spirit adhere to the soldering-iron it is not hot enough. An hour's practice should teach one the proper temperature at which to use the bit.

In soldering zinc or galvanised iron, if the soldering-bit is too hot the joint will be very rough on account of some of the zinc being melted from the surface of sheet and mixing in the solder. For tarnished zinc and galvanised iron, the spirits should not be quite "dead," that is, the scrap zinc should be withdrawn from the acid before the boiling action has quite ceased. It is, perhaps, a better plan, though, to freshen up the "killed spirits" by adding a small quantity of neat acid.

In soldering zinc or galvanised iron, if the soldering-bit is too hot the joint will be very rough on account of some of the zinc being melted from the surface of sheet and mixing in the solder. For tarnished zinc and galvanised iron, the spirits should not be quite "dead," that is, the scrap zinc should be withdrawn from the acid before the boiling action has quite ceased. It is, perhaps, a better plan, though, to freshen up the "killed spirits" by adding a small quantity of neat acid.

In soldering copper, brass, and black iron, the edges of metal should be carefully cleaned before the lap is formed. One of the tests of a good soldered joint is that the solder shall have run right through the joint, and if this be done, and the joint properly cleaned with soda and water, there is little danger of corrosion from the use of chloride of zinc. The great drawback to the use of this flux is in the corroding action that takes place if any be left about the joint; perhaps the chief evil being when it is not properly driven out from between the laps with the running solder.

The sketches of joints shown are enlarged somewhat, to better exhibit the layers of metal. (1) shows the ordinary lap-joint, as used in soldering together the edges of tinplate, zinc, or galvanised iron, the width of lap running from about 1/8 in. in thin tinplate up to ¼ in. in galvanised iron.

To make a soldered joint is not a very difficult matter; but there are a few things that want to be taken notice of if the job is to be carried out successfully. The fluxes (anything that is used to assist the flow of metals) used are various; but those commonly in use are "killed spirits," and ready-prepared soldering fluids. "Killed spirits," or "spirits of salts," as it called, takes a good deal of beating for all-round work, as by its use almost any metal can be soldered, with the exception, perhaps, of aluminium. It is prepared by dissolving as much scrap zinc as possible in hydrochloric acid, the resulting liquid being known chemically as a solution of chloride of zinc. If the edges of the metal are clean, they can be lapped over without any preparation, and the spirits applied along the joint with a brush about 1/8 in. wide - a good brush can be made with a few bristles fixed into a strip of double-over tinplate. Before using the soldering-bit it should be seen that it is

properly tinned, and if not, get to dark-red heat, file the point about | in. along, dip in spirits, and then apply solder.

properly tinned, and if not, get to dark-red heat, file the point about | in. along, dip in spirits, and then apply solder.The mistake that the novice usually makes in soldering a joint is to stick the metal on like glue or putty, instead of holding the soldering-iron long enough against the joint for the solder to be properly melted and the joint to get sufficiently hot for the solder and sheet metal to firmly adhere together. Instead of using the extreme point of

the soldering-iron to run the solder on joint, an edge of the square point should be used to draw along the solder. In this way a greater quantity of heat will be transmitted to the joint, and thus a better and quicker job made.

the soldering-iron to run the solder on joint, an edge of the square point should be used to draw along the solder. In this way a greater quantity of heat will be transmitted to the joint, and thus a better and quicker job made.The soldering-iron must be watched, so that it does not get red-hot, or else the tinning on its point will be burnt off, or, what is worse, form a hard skin of bronze, which is somewhat difficult to file away. When the soldering-iron is drawn from the fire it can be cleaned by quickly dipping the point into the spirits, and also in this way one can judge as to its proper temperature. If when dipping the iron into the spirits much smoke is given off, or the liquid spurts about, the iron is too hot; or, on the other hand, if small bubbles of spirit adhere to the soldering-iron it is not hot enough. An hour's practice should teach one the proper temperature at which to use the bit.

In soldering zinc or galvanised iron, if the soldering-bit is too hot the joint will be very rough on account of some of the zinc being melted from the surface of sheet and mixing in the solder. For tarnished zinc and galvanised iron, the spirits should not be quite "dead," that is, the scrap zinc should be withdrawn from the acid before the boiling action has quite ceased. It is, perhaps, a better plan, though, to freshen up the "killed spirits" by adding a small quantity of neat acid.

In soldering zinc or galvanised iron, if the soldering-bit is too hot the joint will be very rough on account of some of the zinc being melted from the surface of sheet and mixing in the solder. For tarnished zinc and galvanised iron, the spirits should not be quite "dead," that is, the scrap zinc should be withdrawn from the acid before the boiling action has quite ceased. It is, perhaps, a better plan, though, to freshen up the "killed spirits" by adding a small quantity of neat acid.In soldering copper, brass, and black iron, the edges of metal should be carefully cleaned before the lap is formed. One of the tests of a good soldered joint is that the solder shall have run right through the joint, and if this be done, and the joint properly cleaned with soda and water, there is little danger of corrosion from the use of chloride of zinc. The great drawback to the use of this flux is in the corroding action that takes place if any be left about the joint; perhaps the chief evil being when it is not properly driven out from between the laps with the running solder.

No comments:

Post a Comment